Dying Days at the Guest House

By Celeyce Matthews

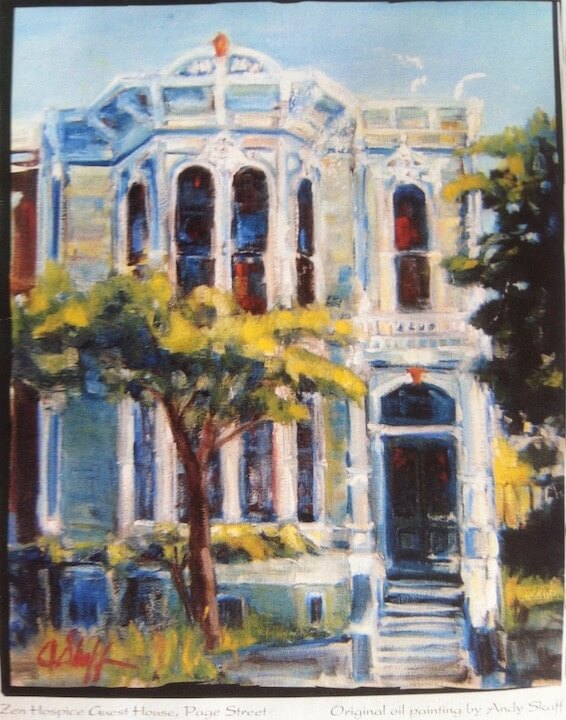

Although I love my new job as a neonatal intensive care nurse, I miss my work in hospice on a daily basis. Before I was a NICU nurse, I was a certified hospice and palliative care nurse assistant at Zen Hospice Project’s now-defunct Guest House. The Guest House was a six-bed hospice residence in an iconic Victorian home in San Francisco, caring for people at the end of life. In its own last year of life, the Guest House had fewer and fewer residents due to complex political and financial issues. While it was extremely painful and frustrating to watch that beautiful place slowly die after serving as a graceful home of living and dying for more than 30 years, its decline also afforded some exceptional experiences that I will forever be grateful for. And frankly wonder if will ever be matched in meaning and beauty.

Some weeks that last year we only had a couple of residents at the Guest House, and in my 12-hour shifts, I was able to spend significant time with people in their final days and minutes and be with them as they took their last breath. While there are some similarities between the NICU and hospice, the beginnings and ends of life, the intense clinical pace of the NICU does not allow for the meaningfulness of the work to register as keenly as the spaciousness of the Guest House allowed for, especially in its final year. The deep sense of peace mixed with the shared experiences of love, anguish, sadness, suffering, beauty, and gratitude as I cared for people letting go of life was profound. Real and raw, in the midst of truth and complexity, love, and pain, I found passionate equanimity; I found a home.

“Alan” was chatty the first day I met him. Jittery in his movements, his emaciated limbs shaking in his grand, arching gestures, he told me stories of growing up gay and black in an area of the country not welcoming of these identities. He rarely paused between his words, so incessant was his need to talk, to speak his life as it was slipping away. In the next days, he became silent but insisted on sitting upright on the side of his bed. His long, ethereal body precariously balanced, wavering as if just about to collapse, his eyes half-closed, teetering on the edge. He would sit like this all day, only willing to get in bed to be gently bathed. He also wanted basketball games to be continually on his television. Concerned about him falling, and because I had the time with only one other resident in the house who was being looked after by the other caregiver, I spent hours just sitting with Alan in his room. He seemed to be hovering in a liminal space, not fully here but not gone, as the sounds of a basketball game, the sounds of life, quietly played on in the otherwise quiet room.

As I sat with him, I became attuned to him, knowing when he was about to reach for a tissue to wipe his leaking mouth and handing it to him just as he lifted his hand. Occasionally he would become aware of me and turn toward me and say, “Oh, you’re still here.” “Yes,” I’d say, “Is that ok with you?” “Yeah, thank you,” he would sometimes say, sometimes only finding the energy to nod slowly. In that quiet drama of stillness and basketball and afternoon light and Alan’s struggle to stay upright wavering between life and death, I felt a deep human kinship and connection between us. Our differing backgrounds and current circumstances dissolved in the reality of approaching death. At the rawest and most stripped-down level that the end of life brings, we were just two humans sitting together on the precipice.

And the caring – caring about this man I didn’t really know, caring for his body in ways that he could no longer do for himself – caregiving felt like a sacred thing, one that nourished me deeply. Bathing the dying, changing their briefs, feeding them, receiving their life stories, holding their hands felt like an incredible privilege to me. In a way, I needed it as much as they did. I miss this every single day.

The last time I saw Alan, he had finally consented to lying safely in his bed, no longer able to sit upright on his own at all. It was a busier day, and I didn’t have as much time to sit with him. When I came to say goodbye and tell him that I was going out of town for a week, we both clearly understand that this was goodbye forever. He started to cry and reached for me. I think this was the moment that the closeness of his death became even more starkly clear to him; the chronicling of the lasts and the losses getting close to the bottom of the page. He thanked me, and I could again feel the care and connection between two humans flow between us. I hugged him and quietly beamed my love and gratitude to him, marveling at how loss, love, and sadness are woven into the fabric of life. I was sorry to not be there for his death.

To not flee from these realities of humanity, of life, love, and loss, to stay with them unflinchingly was my job, but more importantly, it is my calling.

Being in the highly clinical and yet heart-centered world of the NICU, these aspects of care can feel sometimes eclipsed by the intense technology and the often breakneck pace. But the moments of placing a sick premature baby on his mother’s bare breast for the first time, or teaching a new father how to change the diapers of his 3 pound baby, or holding and bottle feeding a cute growing baby, I feel the gifts of caregiving. The clinical demands of the NICU are not what I ever wanted to be involved in, but those tiny, fragile babies seduced me.

And so here I am, at the other end of life, the beginning. One day I will have to return to hospice, I truly do miss it daily. Although I may never be gifted with the spaciousness of time to just be humans together living and dying, and engage in slow, gentle, mindful care as I was lucky to do in the dying days of the Zen Hospice Project’s Guest House.