volunteer

Family Caregiver Burnout

When my own mother was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer in January, I thought, “well, at least I have been immersed in grief and loss studies for more than 20 years.” I have run support groups for families who have experienced the death of a child for more than 18 years. My father died when I was a child. One of my daughter’s died at birth. And here I am now, working for an organization that teaches mindful caregiving. I am surrounded by mindful caregivers. So really, how hard can this be? I am grateful to have an understanding employer who supports my need to have a flexible work schedule in order to accommodate the need for me to travel back and forth to care for my mother during this difficult journey.

Can it really be that hard?

Well, it likely won’t come as a surprise that it is indeed excruciatingly hard, especially for a person who excels at pouring myself into helping others. I excel at giving 150% of everything I have to everyone else. And so what this really and truly means is that I am terrible at giving 100% to myself in times of need.

I have had to shift my thinking dramatically, and I have had to set some of my own guideposts. One question I am thinking about is this: What accommodations do I need to make in order to care for myself so that I can better care for someone else? I recognize that my strength is in caring for others, but my weakness is in caring for myself. I’ve started my own personal list, and I’d love for you to reach out to me and tell me how you continue to care for yourself if this is a struggle for you as well.

Here is my own personal list:

Add reminders to my phone using timers to tell me to take five minutes to breathe. Before I get out of bed in the morning, envision the boxes in my brain and peek inside: If it’s a work day today, take a moment to look inside my mental health box: acknowledge the anxiety I feel about the changes in my mom’s eating and pain level, and then close up the box until the end of the day when I can peek inside again.

Send a text to my mom who lives in a different state: How did you sleep last night? Wait for her response; read it; then tuck it away until evening when I can text her again.

Stay hydrated! Fill up my water bottle so I can drink water all day. Refill it as needed. Practice, practice, practice breathing. Remind myself it’s a practice not a destination. Keep practicing.

Join me in starting your own list. And send me a note to tell me what’s on yours. –Sarah

A day in the life of a family caregiver

6:37 a.m.

A light scratching against the door and the morning light coming through the edges of the shades awoke me before my alarm had the chance to go off. You don’t get fed until 7:30 a.m., I mumbled to the cat as she continued to mew. It was Wednesday morning, the last day of classes for my graduating senior.

I grabbed my phone to see if there were any messages from the east coast where some of my family live. Silent. Whew, I thought. No emergencies overnight.

I jumped out of bed, ran into the laundry room to start a load of laundry, pushed the coffee maker button, and opened the fridge to see what I might find to make my son for breakfast on his last day of school.

The morning routine is pretty, well, routine:

Feed the cats.

Feed the dogs.

Feed the kid.

Give the animals fresh water.

Toss a load of laundry into the dryer and a load into the washer.

Walk the dogs.

Kiss my husband goodbye as he leaves for work.

Text my mom who just enrolled in hospice to see if she slept well and how her pain was on a scale of 0 to 10. A two. Great, I wrote back. The daily pain meds should bring that back down to a zero in an hour or so. I’ll check back in a bit later today.

Pour coffee.

Get a glass of water.

Time for a real breakfast or just grab a protein bar? I check my watch.

Several meetings at work today mean less time to meet some deadlines so I head into my home office a bit earlier.

Get a text from my son at school. Did you buy me a yearbook?

Yes, I respond.

They don’t have a record of it, he writes back.

Go ahead and buy one, and I’ll Venmo you the money later, I reply.

The day goes on like this. If I’m lucky, I get to step away long enough to take the dogs for a quick mid-afternoon walk around the neighborhood. In my head, I’m balancing work, my aging mother’s care, my son’s needs, and even the needs of the aging neighbors around me. Occasionally, when I go out to get my mail or pull in my garbage cans, my neighbor will ask for IT support. She’s in her 70s and often wants to communicate with her daughter in England but struggles sometimes with how to do that.

I am a caregiver. My oldest will turn 27 when my youngest goes off to college in the fall. For 27 years there has been someone in my house to take care of. And now, my mother needs more care so I find myself flying up and down the west coast more often. I am a family caregiver. And I am a lucky caregiver because I have the advantage of working from home, taking a moment during the day to respond to the needs of my mother–the hospice nurse may call; the social worker calls sometimes; my mother

calls.

My needs get set aside. Often I am the last one to stop to care for myself. The dog walks, in many ways, are self-care. I can breathe fresh air, I can take a moment to regroup my thoughts. But even then, I’m caring for the pets. The real needs for my own self-care get pushed to the side so often I pause and ask myself: If I were watching me from afar, what would I tell myself?

Stop.

Pause.

Feel the water over my hands as I wash them.

Notice the soap as I hold it in my palm, the lavender pieces acting as a loofah.

Rinse.

Breathe.

Step back into work.

Place everything else into a container in my head and close it up for now.

Find gratitude for who I am and what I do.

I am a family caregiver.

I too need care and nurturing.

How am I feeling?

Notice the feeling.

Acknowledge the feeling.

Thank the feeling.

Breathe.

Begin where I am. Take one breath, and I will go from there

Boundaries.

Boundaries–It’s a word filled with lots of expectations and hopes–especially when one thinks about it within the context of caregiving. It is easy to understand the boundary of a property line–a fence, a sidewalk, or even a gate. It is, however, much more difficult to understand and navigate emotional boundaries surrounding caregiving.

Brené Brown, social science researcher and professor, defines them in this way: “boundaries are a prerequisite for compassion and empathy. We can’t connect with someone unless we’re clear about where we end and they begin. If there’s no autonomy between people, then there’s no compassion or empathy, just enmeshment.”

It’s the perfect definition for caregivers and for the work that we do at Zen Caregiving Project. In order to have compassion and empathy, one must define their own boundaries. While this is always easier said than done, we offer a few tools to make sure that you honor your own boundaries.

“Using the S.T.O.P. practice, we encourage caregivers to Stop or pause when they notice someone has crossed an emotional boundary. Then, Take a breath and notice where emotions are being expressed in the body. Observe and consider what just happened. And finally, once you’ve taken a moment to do those three things, Proceed in a skillful way that does not make a tense situation worse.”

Managing healthy boundaries in a caregiving relationship can be difficult and uncomfortable. Please remember, whatever you do, however you respond, be kind to yourself.

When a ZCP Staff Member Finds Herself in the Role of Family Caregiver

The recent call came on a Sunday night around 11:00 pm from my mother’s cell phone. Except it wasn’t my mother on the other end–it was a friend of hers.

“Hi, Sarah, this is Pat, and I’m in the ER with your mom, and it’s not good.”

Six hours later I was on a flight to Orange County, California where my mother lives. Within 12 hours of that call, I was in the hospital room with her when the doctor came in to tell us, “It’s stage four cancer that has spread to several places.”

The next several days in the hospital are honestly a blur – oncologists, urologists, palliative care, “ovarian cancer,” “no, possibly, uterine cancer,” “no, likely pancreatic cancer.” Pain medication, more tests, more doctors, PAs, nurses, and on and on and on.

Three weeks beyond that phone call, and I could finally take a breath, for a moment, to think about how I went from getting ready on a Sunday evening for a week of work and my son’s school activities, to finding myself as a caregiver for my aging mother and talking each evening to my family over Zoom from 1,200 miles away.

So this is what they mean by Sandwich Caregiving, I thought to myself as I responded to work emails late into the night and emailed my book club to let them know I’d be out of town for an extended period of time and would step away for the time being from attending (or hosting) book club.

One phone call. Twelve hours. 1,200 miles. And everything in my life (and my mother’s!) had been turned upside down.

By week four as we began to settle into our “new normal,” I began to remember what I had learned in the first Essentials of Mindful Caregiving course I took shortly after joining Zen Caregiving Project.

Pause for just a moment in the doorway.

Take a breath.

Feel the water over my hands as I wash them in between caregiving duties.

Breathe in.

Breathe out.

Focus on my breath.

The S.T.O.P. Practice

Stop.

Take a breath.

Observe my environment.

Proceed with my activity.

I have an emotional toolkit, I reminded myself as I put a variety of pills into my mom’s new four times a day pill organizer.

Over and over again for the past two months, I am reminded of the value of these courses that we teach. I am also reminded how important it is to remind the caregiver to practice self-care.

After I tucked my mom into bed at about 8:30 pm during my fourth week, I was reminded of my own need for self-care as I went into the kitchen to get a glass of water and instead sat down at the table for a moment and promptly fell asleep for more than an hour waking up with an imprint of my mom’s placemat on my cheek.

The dishes can wait, I whispered to myself as I crawled into bed to sleep a few hours before the alarm went off to give my mom her 2 a.m. medication.

Breathe in.

Breathe out.

Tomorrow, I thought, tomorrow, I’ll practice being as kind to myself as I have been to my mother. I can do at least this much.

Heidi Hartsough’s journey from the Peace Corps to ZCP Volunteer

Heidi Hartsough lights up a room when she steps into it. Her smile, even when talking about grief and loss, is ever present, and when she talks about her volunteer work with Zen Caregiving Project (ZCP), an easiness and lightness appear. In many ways, Heidi has been called to ZCP as a volunteer at Laguna Honda Hospital where she offers her presence five hours a week sitting with residents and families.

As a registered nurse at UCSF Medical Center, Heidi understands what happens in the medical system as a patient, but her roles as an RN and a volunteer are vastly different.

“When I start my 13-hour shift at the hospital, I just jump in, doing, doing, doing, and there is no check-in or space to just be. My job is doing all the time.”

“At ZCP it’s simply about being. I love when I put on my lanyard that says Volunteer, and I can enter a room and offer my presence. These experiences complement one another, and I have grown from being a nurse and a volunteer,” Heidi continues.

Her journey to ZCP started at a young age with parents who instilled in her the value of giving back to her community. The daughter of Quaker parents, Heidi grew up in San Francisco.

“I know that my childhood and how I was raised were hugely influenced by service. My parents saw everyone as equal, and I learned early that a person should show up to be all that they can be,” she explained.

Indeed, Heidi showed up early for service when she followed in her mother’s footsteps and joined the Peace Corps after studying public health in college. She spent three and a half years in Kouloumi, Togo in Western Africa, a small village located between Ghana and Nigeria. It was there, living with a midwife and working with the villagers, that she felt called to be a nurse with a focus on women and maternal health.

“The traditional way in which death and birth were held in Togo and how death was so accepted as a part of existence made a huge impression on me. We don’t talk about stillbirth, neonatal loss, or infant birth in America,” she explained.

In Africa, when asked the question, “ ‘How many children do you have?’ The answer was always followed by, “Oh, I have eight children and three are living.”

That was an answer she’d never heard before in America. “The traditional way in which death and birth were held and how death was so accepted as a part of existence made a huge impression on me,” she said.

Like many professionals with children, Heidi began to find a few extra hours available each week as her children grew older. She knew she wanted to do meaningful volunteer work, and that’s how she came across the Zen Caregiving Project.

“My parents were getting older, and I wanted to explore how I could gain more experience and knowledge as a mother and a daughter,” she said. “It felt amazingly natural as a labor and delivery nurse and my desire for service to volunteer with an organization like ZCP.”

At Laguna Honda Hospital (LHH) in their palliative care ward, Heidi was struck by the fact that we are all just human beings sitting together with stories to tell.

“To be in community with one another, to be in the presence of someone else even when we don’t communicate, is powerful,” she explained. “We are meant to practice loving kindness with one another, and this work has made me a much more grounded person and keen to sit with curiosity and patience to see what unfolds in everyday interactions.”

“As volunteers, we are present at our most vulnerable with those who are at their most vulnerable; we should not shy away from that,” she continues.

Heidi surprised herself early on after leaving her volunteer shift at LHH. “Each time I left my shift at Laguna Honda, I felt energized and connected even when someone had just died. The way death was framed in my Peace Corps days influenced this,” she said.

“We need to talk about death more often,” Heidi said. And at Zen Caregiving Project that’s exactly what she does.

On the wall behind Heidi, there is a painting of four blue hands with white dots on them. They appear to be hands raised as if waiting their turn to be next. “Come Heidi, sit with me. Be with me,” the art suggests.

May we all be fortunate enough to have a Heidi by our side when our time comes.

If you like what you read, please join us and enroll in one of our courses, share our work with someone you think will benefit from it, or support us through a donation.

Collaboration in Action: ZCP Volunteers and Curry Senior Center

The streets of San Francisco’s Tenderloin district can appear to be a cacophony of poverty and human suffering: crowded, dirty streets, the occasional smell of urine and feces, a barefoot person huddled on the sidewalk, their meager belongings strewn about them, tents, open drug use. For some, with nowhere else to go, the street is their home; they live their lives in public.

For others, who inhabit small, cramped rooms in single room occupancy hotels—SROs—the street may be their living room, a meeting place, a hang out, a social center, the hub of their social life.

On a crowded block of Eddy Street, across from the Tenderloin Police Station, stands San Francisco Historical Building #176, home of the Cadillac Hotel.

For the past year, Zen Caregiving Project (ZCP) volunteers have been going to the Cadillac every Friday to provide emotional and social support for the residents living there. The intention is to be able to provide palliative support for residents who are ill and wish to die at home in their room. The first step, however, is getting to know the residents, gaining their trust, and becoming familiar with the culture of the hotel.

Our work is a collaboration between Zen Caregiving Project and Curry Senior Services, which has been providing a variety of wellness programs at the Cadillac for the past five years.

The resident population is diverse. Of the 150 rooms, 75% of the population is over the age of 55, 43% are Spanish speaking. Some work regular jobs and go out every day and some rarely leave their rooms. Some are disabled, some show no physical indication of poor health but bear the scars of trauma, addiction, and mental health struggles. And they all have stories, colorful, astounding, heartbreaking stories. ZCP volunteers listen; we are witnesses to whatever the residents want to share about themselves, their lives.

One of our volunteer caregivers, John Ungvarsky said, “We’ve been able to connect with many of the residents at the Cadillac Hotel and provide a presence for them. Just by being present and being able to listen to them, we are building relationships.” At Zen Caregiving Project we embrace the notion of the mutuality of service, so that witnessing and companioning become a mutual process that serves the needs of both residents and volunteers.

A Volunteer Caregiver at the Cadillac Hotel Finds Meaning in the Tenderloin

John Ungvarsky is a thoughtful, contemplative environmental scientist who retired from the Environmental Protection Agency in August 2022, and in October 2022 he began his training at Zen Caregiving Project to become a volunteer caregiver at the Cadillac Hotel in the Tenderloin.

“Anybody who has spent time in San Francisco is aware of the Tenderloin,” John said. “It doesn’t have a good reputation. It’s not the kind of place where people want to spend a lot of time. It’s in the news about fentanyl deaths, homelessness, and more.”

While John knew he wanted to serve in the capacity as a volunteer caregiver, he wasn’t sure what to expect at the Cadillac Hotel. But John also knew that there was a great need to serve there because of all of the people who are suffering, and he was open to seeing how his service would unfold.

John spends up to five hours a week at the Cadillac Hotel meeting with residents, listening to their stories and finding ways to connect with them.

In 2006, John was present with his mother when she died, and in 2016, he found himself sitting with his brother, an alcoholic, as he passed away. He discovered in both situations that being present with them as they died were some of the most powerful moments in his life. So he knew, when he retired, he’d want to find ways to sit with others in times of need.

At the Cadillac Hotel, there are elderly sick people but also a great number of middle-aged and young people. Many of the residents have been affected by poverty, homelessness, drugs, alcohol, and/or mental illness and have a desire to stay off of the streets.

They’ve been through some very difficult periods of their life that have led them to live there. They are isolated, and some don’t get out much. They feel safer being in the Cadillac.

At first, John explained, the residents wondered what the volunteers wanted from them. They were certain that there must be some kind of transactional relationship. But given time and consistent presence, John explained that they have been very successful at building trust.

“We are welcomed each Friday, and we are having a very positive impact on the residents,” he said. “It is a gift because it is teaching me so much about myself. We are touching their lives and they are touching ours.”

John acknowledges that it has been a surprise for him at how comfortable he feels being around the residents.

“Zen Caregiving Project offers us an opportunity to connect with people in need, and the most important quality for us as caregivers is being vulnerable with the residents, and in turn, they can be vulnerable with us.”

Loretta Lowrey’s Practice As Service to Others

Thirty years is a long time to be in a relationship with anyone, let alone with an organization that you volunteer for. Loretta Lowrey arrived at Zen Caregiver Project (then known as Zen Hospice Project) as a volunteer in 1992, and while she stepped away during a few child-raising years and then again during her busy career years, Loretta has always found herself being called back to the organization in one way or another.

She came to Zen Caregiving Project (ZCP) in the middle of the AIDS epidemic when even the word ‘hospice’ was new to her.

“Suddenly, everyone in my world was talking about it—the woman who took care of my daughter, my sister, a museum curator that I worked with,” Loretta said. “When something presents itself to me three or more times, I pay attention to it.”

Paying attention is exactly what she did by volunteering at Laguna Honda Hospital as a Zen Caregiving Project caregiver. She continued in that role for five years until her second child turned two years old; she then stepped away to spend more time with her children. Because of her background in nonprofit management and development, Loretta continued to stay active with the organization by occasionally helping with events and development support. Over those years of being a full-time mom and employee, Loretta lost touch with ZCP for a while.

In 2013 when Loretta was looking forward to retirement, she decided it was time to return.

It felt like coming home,” she said. “When I returned to Laguna Honda Hospital (LHH) as a volunteer, it felt so familiar and lovely to be a part of that again. We all live in these self-created bubbles and the greatest impact for me has been meeting the range of people who have invited me into their lives and into their hearts.”

Observing the frailty and resilience of the residents is what continues to open Loretta up to becoming more compassionate and open-hearted.

“It’s given me perspective on what is truly important. Volunteering at the hospital and being with residents is so real. So many other things that seemed important before dropping away. It motivates me to live more fully by being exposed to illness and death and having it normalized,” Loretta said.

One of the residents who made an impact on Loretta was a woman who used a device to speak. The only way that she could communicate was by typing out words and since it was difficult to use her hands, it took a long time for her to have “a conversation.”

“I was so taken aback that it was such an effort to communicate, yet she would say things like ‘That’s such a pretty dress.’ We laughed and cried together while completing a legacy project that was important to her.”

During the pandemic, Loretta became a Mindful Caregiving Education (MCE) instructor for ZCP. She now teaches some of the MCE courses and still sits with residents at LHH. Through the years and through her various roles with ZCP, Loretta has become more aware of herself.

“One thing I am able to notice is when I’m acting out a role or when I have my armor on. The training we’ve had to sit at the bedside with someone has made me more aware of the power of presence,” Loretta said.

“I really think of this work as part of my practice. I think of service as seeing the wholeness in others. I thought I’d be coming to this work to give something, but in fact, I take away so much more than I give.

“Many of these residents are living fully in spite of their illness or condition,” Loretta said. “They are such a gift to me.”

And Loretta, like all our volunteers, is a gift to us at Zen Caregiving Project.

If you like what you read, please join us and enroll in one of our courses, share our work with someone you think will benefit from it, or support us through a donation.

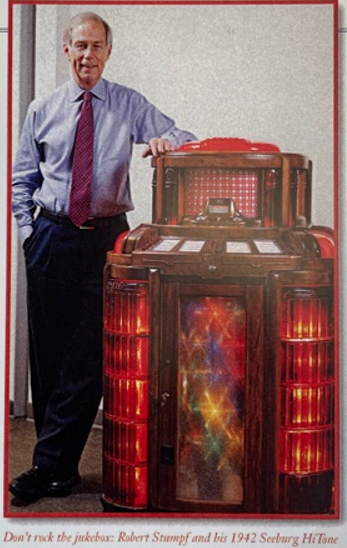

Bob Stumpf, ZCP Volunteer since 2016

Bob Stumpf is prepared to go the distance whether it’s in a relationship with others or on a run. He’s completed 28 marathons and these days, Bob often comes in first or second in his age group. (Don’t tell anyone that at 74 years of age, Bob generally competes against only one or two others in his age category).

As a volunteer with Zen Caregiving Project (ZCP) for nearly six years, Bob sits with residents at Laguna Honda Hospital every Friday afternoon. One particular resident continues to enrich Bob’s life even though this person has since died.

“There was a resident at Laguna Honda that I visited weekly,” Bob explained. “I would save him for last because I knew it would be an uplifting experience for me at the end of my day.”

Bob explained that he loves sports and thought he knew everything there was to know until he met S, that is. “S. knew everything there was to know about sports, everything. He and I also bet on sporting events, usually hundreds of thousands of dollars at a time, with play money. I think he still owes me some money,” Bob said with a grin.

“Sports were a common bond from the beginning, and S. had also visited my hometown in Southern Indiana, so he understood where I came from,” Bob said. “It wasn’t just me taking care of him; it was S. taking care of me.”

That’s one aspect that surprised Bob about being a volunteer – how much he would get back from it.

“Not only have I gotten close to the residents I sit with, but I’ve developed close, personal relationships with other volunteers. During our shift change meetings, I find myself getting to know other volunteers who are very different from me, and yet we are kindred spirits,” Bob said.

“I didn’t expect that whatever calls people to do this work would give me the opportunity to meet so many other like-minded folks. We’re a real community.”

As a left-brained attorney for more than 40 years, Bob surprised himself by recognizing that he can also be a right-brained kind of person. When he turned 65 years old, he wanted to scale back his work and increase his volunteerism. While he had been on a number of charitable boards over the years, he found himself drawn toward volunteer work that would give him a one-to-one connection.

“I’ve always been interested in the concept of death; not in any kind of morbid way, but in the sense that we are born, we live, and then we die.”

Bob is also interested in music; specifically, he has a penchant for collecting jukeboxes. He once had 22 jukeboxes in his office that are now at home with so many others that he doesn’t divulge the total number. There’s one behind him as we talk, lit up and ready for any song to be played.

“They all work,” he explained. After he purchases them, he sends them to someone who restores and fixes them for him and then delivers them wrapped up in such a way that Bob feels like it’s Christmas morning every time one arrives.

He feels that same joy when he leaves his shift at Laguna Honda.

“I get so much more out of volunteering than I put into it,” Bob said. “When 6 p.m rolls around on Friday, I’m always at my happiest as I’ve been all week. During my shift, I’m able to get out of my own head. It’s a cleansing and nourishing experience.”

“I’m more sensitive now to the importance of having relationships with people who are really not like me at all,” Bob said.

One such resident that Bob has met could not be more different. Bob has had many advantages as a white man who attended Harvard, whereas E. had a very different life as a black man in America who for many years lived on the streets. Bob and E. have met weekly since December 2016, and they have forged a strong relationship.

“He’s important to me,” Bob explained. “ We aren’t family; we aren’t best friends, but we get together weekly, and he’s my friend. When I leave, he usually says, ‘Be safe out there.”

Bob looks off into the distance and returns to thoughts of his friend, S. who died last year.

“I saw him for almost two years,” he said, “and every time I walk by his room at Laguna Honda Hospital, I think of S. I miss him.”

Bob hasn’t just run 28 marathons. He’s running a marathon with residents at Laguna Honda, and rest assured, he’ll go the distance with them not to win any kind of medal, but to just be present on their journey. “People can have almost nothing left, and they are still living their lives,” Bob said. Yet they still have Bob, holding their hand and offering his presence. And often, at no extra charge, he offers them a few jokes.

If you like what you read, please join us and enroll in one of our courses, share our work with someone you think will benefit from it, or support us through a donation.

Companionship and Compassion: The benefits of ZCP Volunteers on a palliative care ward

Camille Tacderan is the Daytime Charge Nurse on the South Three (S3) Palliative Care Ward at Laguna Honda Hospital, where ZCP volunteers have served for over 30 years. We spoke to Camille about the value the Volunteer Program brings, her experience of working through the pandemic, and her excitement about the Volunteer Program starting up again.

You have spent many years on the ward with the volunteers. What impact do you see them having?

Residents really benefit from having volunteers on the ward to interact with. It can be as simple as them sitting and talking with a resident in the Great Room [the communal area of the ward], or for some residents who are non-verbal just being present with them or holding their hand. Also, the volunteers are on the ward weekly and often have regular visits with residents whose conditions are changing over time, so they build a relationship with them and can tailor their interaction to that resident’s current needs.

They also support the families of residents. What is special about S3 is that it allows family members to be family members. They don’t have to be medical caregivers and instead can live their own lives and visit as sons and daughters, or spouses. The volunteers are a big part of that specialness because families know that even if they can’t be there to sit with their friends or relatives, the volunteers can be. And that is really reassuring.

For staff, more than anything else, it is just knowing that there is someone to sit with a resident when they aren’t available to do so. As staff, we are looking after a number of patients and sometimes can’t sit with people as long as we would like. Especially when that person is approaching the end of their life, it is comforting to know that the volunteers are available to be with that person in their last moments.

“It is comforting to know that the volunteers are available to be with that person in their last moments.”

You worked through the pandemic when volunteers weren’t able to visit the ward in person. How was that experience for you?

The pandemic was really challenging. On a personal level, there was a lot of anxiety around safety for yourself, your family, the residents, and the other staff on the ward.

The ward closed to visitors and volunteers early in March 2019 to protect residents and stayed closed until mid-2021. During this time a lot of residents didn’t understand what happened, some didn’t recognize staff with masks on, and some clearly missed the interaction they had with volunteers and family. For staff, it was also very difficult as we were busy adapting to new protocols and keeping residents safe, and it was at this time, when we were busier than ever, that it would have been wonderful to have the support of the volunteers who could also be with the residents.

The volunteers have started to come back in person to the ward. How do you feel about that?

I’m really excited as the volunteers are such a big help. We are getting more younger residents joining the ward, who are alert and will be in the ward for a long time so have a big need for social interaction from those around them. With our workload, the staff can’t always provide that level of interaction, which is where the volunteers come in.

Some of these younger residents come to the ward having experienced a lot of social isolation. Some have been living in COVID hotels, experiencing a lack of contact and services. Some have been living alone at home or in an SRO. It is so nice to know that they can get the companionship and interaction they want, need, and deserve when they get to the ward, thanks in a big part to the volunteers.

As the hospital is run by the San Francisco Public Health Department, we are the safety net of the city. Our residents may have been living outdoors on the streets with no family or connections and it is lovely to know that they can come to this ward and spend the last few days, months, or years of their life being cared for and that they knew there were people around them who did care about them.

“What we do on the ward is give the residents love.”

What we do on the ward is give the residents love. They are warm, get three hot meals a day, and get taken care of physically and emotionally. Volunteers are a crucial part of this as they fill the gaps when the staff can’t be there. And that is what makes the ward such a special place.

If you like what you read, please join us and enroll in one of our courses, share our work with someone you think will benefit from it, or support us through a donation.